2022.12.04.

잔느 딜망 (1975, 벨기에)

샹탈 아커만

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

201 minutes

directed & written by Chantal Akerman

Sight & Sound가 얼마 전 발표한 올해의 Greatest Films of All Time 리스트의 1위가 히치콕에서 샹탈 아커만의 잔느 딜망으로 바뀌었다. 아직 못 본 영화라 궁금해서 찾아보았는데 국내에서 볼 수 있는 경로가 영자원이 유일하더라고?.. 어제 예약해서 가려고 했는데 이래저래 못가서 12월 안으로 보면 다행이려나 싶었는데 The Criterion Channel에서 스트리밍 서비스를 제공하고 있어서 오늘 집에서 봤다. 분명히 1시간..까지는 집중해서 봤는데 아무래도 주말에 집에서 보려니까 흐름이 깨져서 (가족과 재활용을 버리러 나가야 한다거나..ㅎ) 201분짜리 영화를 거의 다섯시간에 걸쳐서 본 것 같다. 아쉬운 점은 이 영화의 속도를 그대로 따라가는 것이 또 핵심적인 부분이라고 생각하는데 나는 중간에 멈췄다가 앞으로 다시 돌아갔다가 이러는 바람에 그 체험을 제대로 하지 못했다는 것? 누가 이거 또 재개봉 안해주나 제발 해주길 그럼 영화관에 꼼짝없이 앉아서 201분을 아커만에게 빼앗길 수 있었을텐데.

샹탈 아커만의 다른 작품들이 매우! 궁금하다. The Criterion Channel에 있는 것들을 우선 보고, 다른 보다 최근 작품들도 볼 수 있는 경로를 알아봐야지.

Interview with Chantal Akerman. Paris, April 2009. (link)

Babette Mangolted에 대해서도 얘기한다. 잔느 딜망을 포함해 많은 작품을 함께 했기 때문에 아커만에게 있어서도 중요한 사람이었던 듯.

잔느 딜망에 대한 아이디어는 어느날 밤 찾아왔고 전체를 2주 안에 썼다고. It all came very easily b/c i'd seen it all around me. (excluding the prostitution and murder)

"I made this film to give all these actions that are typically devalued a life in film"

- Delphine was perfect because it had to be someone who won't be normally doing dishes.

- (아커만이 봤던 그녀 주위 여성들 - 이모들 - 의 삶을 말하며) Everything had to be a "ritual"

- 리츄얼이 깨질 때 서스펜스가 쌓인다.

- she has her first orgasm with second client, leading to the burnt potatoes ... and all these destroy ther rhythm and ritual. This orgasm actually destroyed her life, so this is why she killed the third client. to preserve her obsessive world and keep it as it is.

(그러면 다른 살인을 갈등 해소의 도구로 쓰는 여러 작품과는 다르게 여기선 .. so it's not really an act of liberation but showing how important that "ritual" was to Jeanne? 그렇지만 발췌한 글에 보면 아커만이 Chantal Akerman intends that the film be read differently. She has said of the murder, "It was either him or her, and I'm glad it was him." The murder is seen as an act of liberation, one which, Akerman says, "will change her life." 라고 했다는 부분도 있어서. 물론 2009년보다 이전에 한 말이지만)

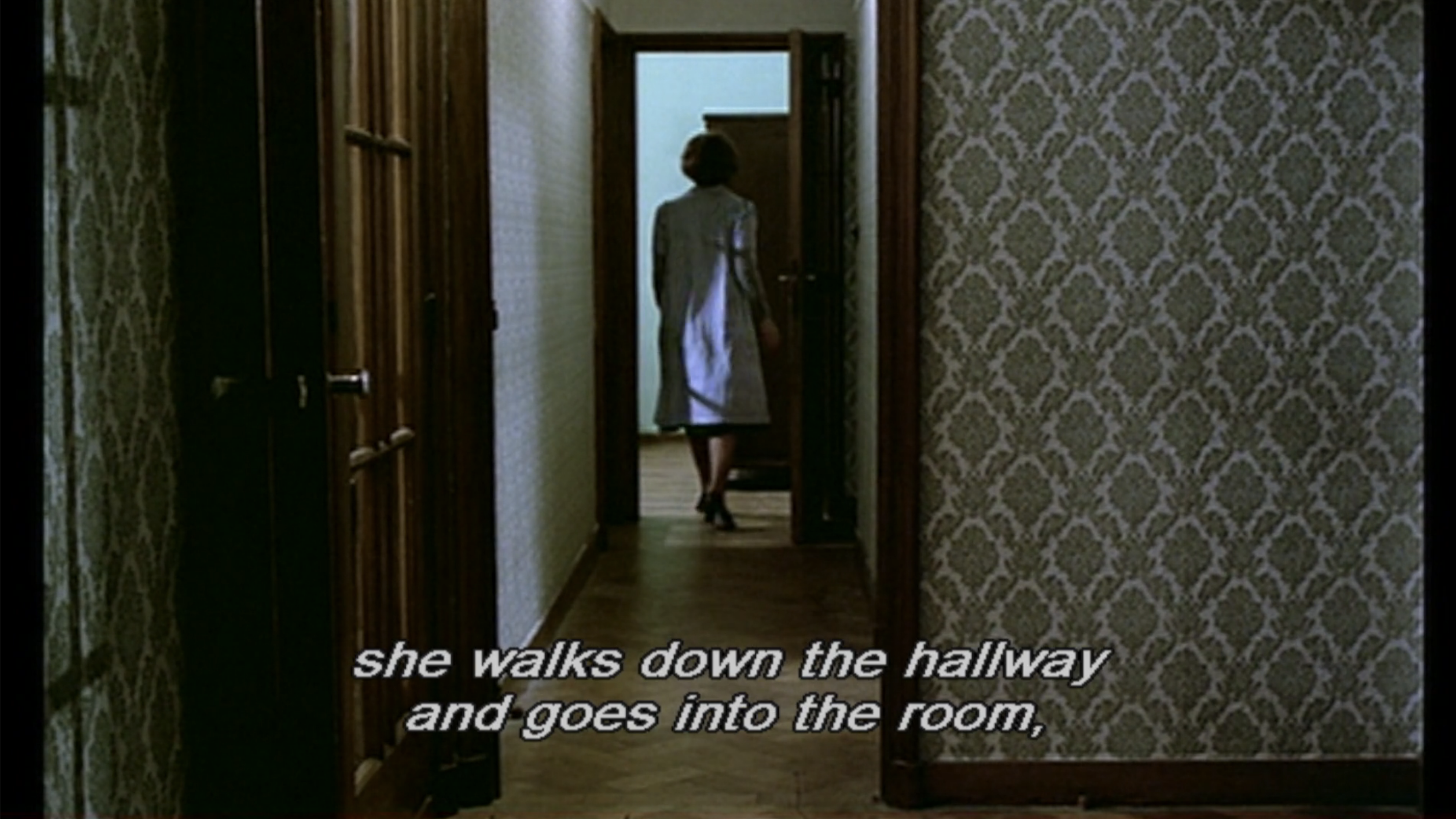

- In all my films I insist there be a hallway and doors and rooms. without them I can't work out the staging. I can manage, but it doesn't come naturally. they help me frame things. they help me work with time.

Framing is very important to me. once the framing had been set, I didn't interfere.

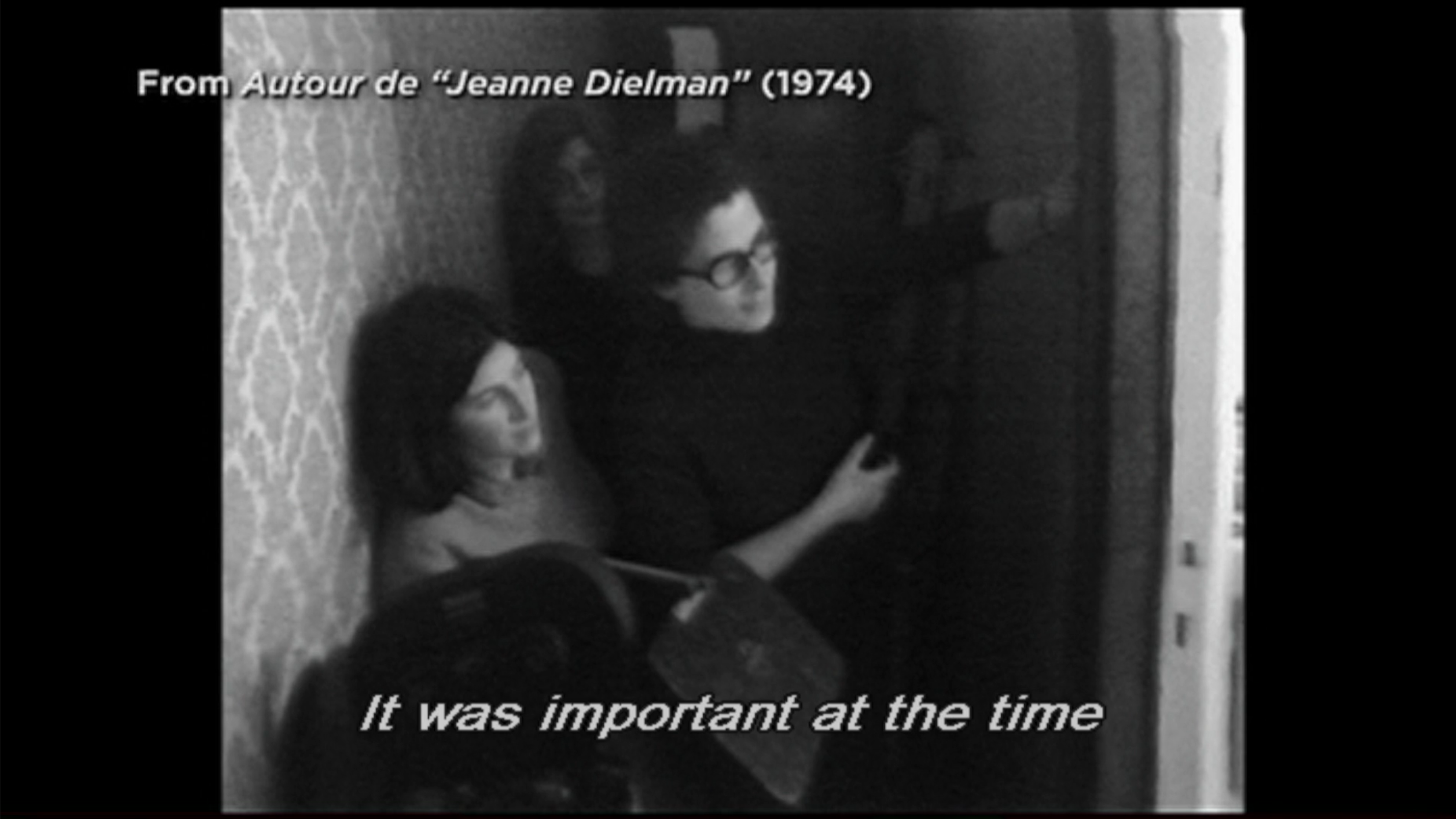

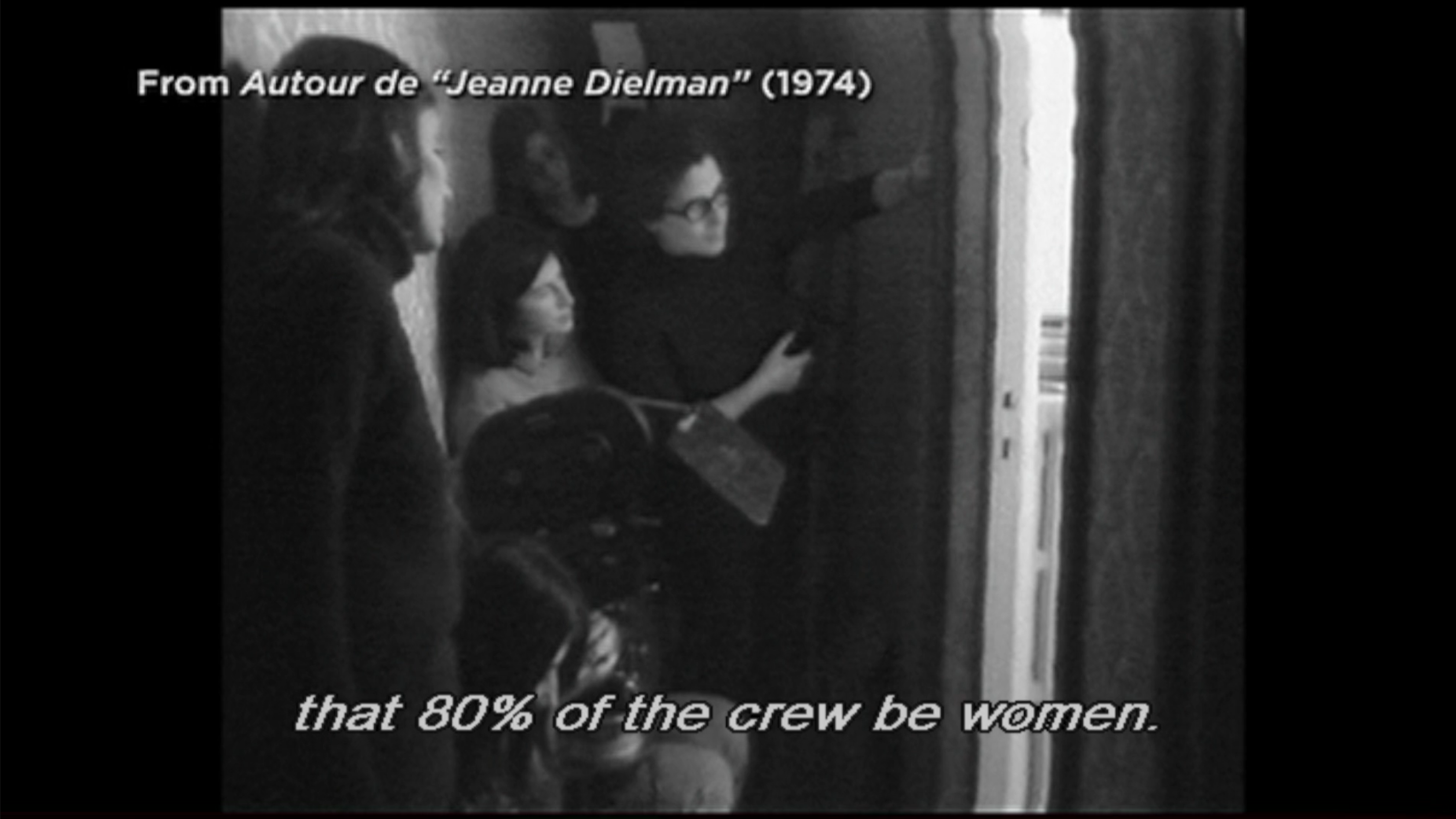

현장에 여성을 두고자 했다는 건 이 인터뷰를 보지 않았다면 몰랐을 사실. 진짜 여러모로 페미니스트였구나.

좋아하는 감독이 생겨 기쁘다...

이하는 잔느 딜망 보면서 캡쳐했던 것들과 관련 비평/리뷰 발췌

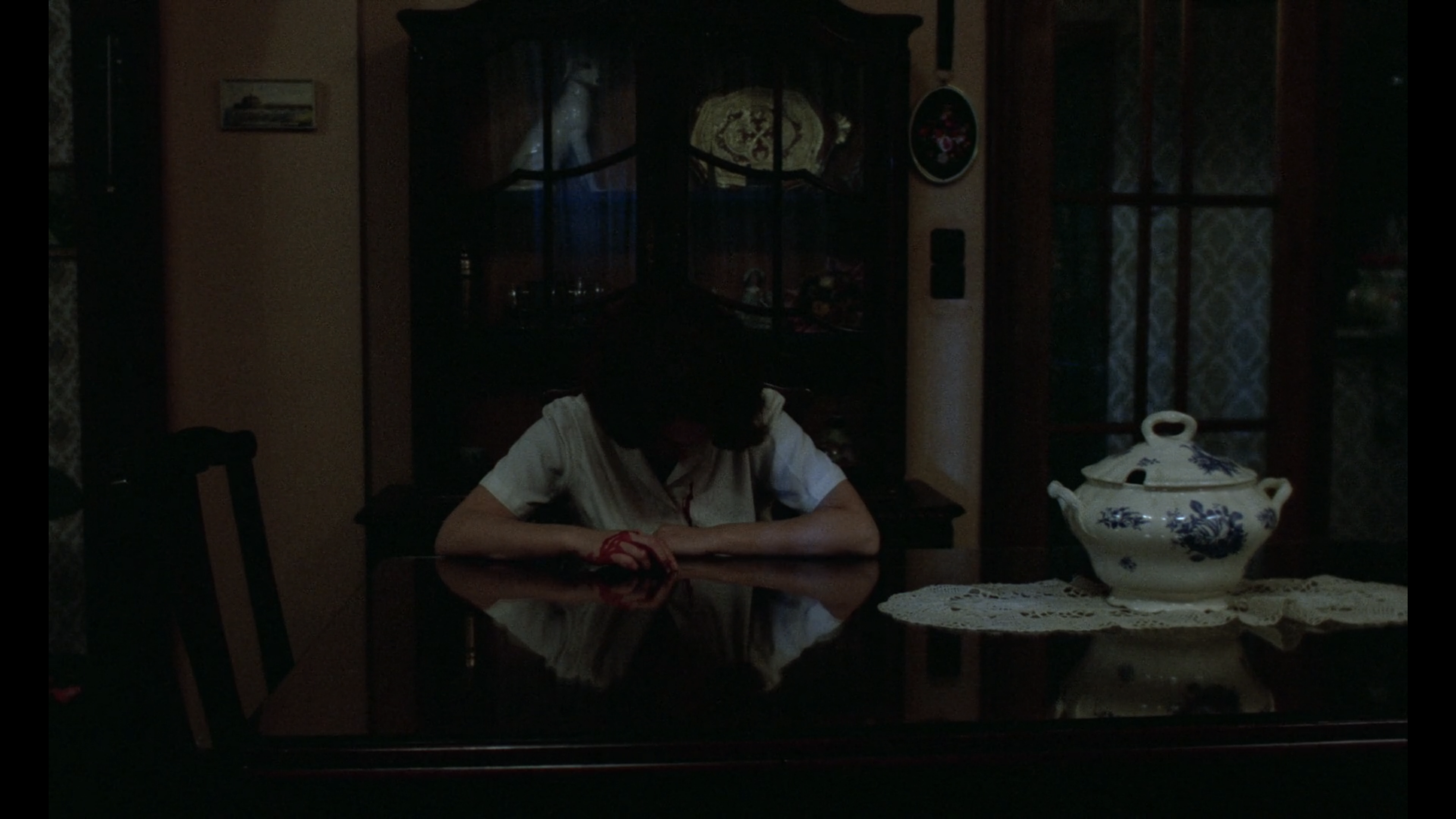

Jeanne gets up, puts on her dressing gown, and chooses her son's clothes. She lights a fire in his room, picks up his shoes and takes them to the kitchen, where she shines them, lights the stove, grinds the coffee beans and makes coffee. She wakes her son; he eats while she dresses. She says goodbye to him, and gives him money taken from a blue and white china crock on the dining table. She washes the dishes, makes her son's bed and folds it into a couch, makes her own bed and lays a towel over her coverlet. She shops and runs errands, returns to her apartment, and begins to prepare dinner. She sits with her neighbor's child, eats her lunch, and returns the baby to its mother. The doorbell rings. [첫날은 여기서 시작] She admits a man, takes his hat and coat, and leads him into the bedroom. She leads him to the front door, gives him his hat and coat, and takes money from him, which she puts in the blue china crock. She opens the window in her bedroom, puts the rumpled towel in the clothes hamper, bathes, cleans the tub, and dresses. She closes the bedroom window and takes dinner off the stove. Her son comes home. They eat dinner immediately: soup, meat and potatoes. She tells him not to read while eating. He puts his books away. She clears the table and helps him with his homework. She knits, and glances through the newspaper, until it is time for them to take their evening walk around the block. They unfold his sofa bed. He reads while she undresses. She turns off the stove, kisses him, turns out the lights, and at last goes to sleep.

Jeanne gets up, puts on her dressing gown, and chooses her son's clothes. She lights a fire in his room, picks up his shoes and takes them to the kitchen, where she shines them, lights the stove, grinds the coffee beans and makes coffee. She wakes her son; he eats while she dresses. She says goodbye to him, and gives him money taken from a blue and white china crock on the dining table. She washes the dishes, makes her son's bed and folds it into a couch, makes her own bed and lays a towel over her coverlet. She shops and runs errands,

returns to her apartment, and begins to prepare dinner. She sits with her neighbor's child, eats her lunch, and returns the baby to its mother.

The doorbell rings. She admits a man, takes his hat and coat, and leads him into the bedroom. She leads him to the front door, gives him his hat and coat, and takes money from him, which she puts in the blue china crock.

She opens the window in her bedroom, puts the rumpled towel in the clothes hamper, bathes, cleans the tub, and dresses. She closes the bedroom window and takes dinner off the stove. .... 해야 하는데 감자가 타버림

감자 든 냄비를 들고 방황하는 잔느

새로 사 온 감자 깎는 장면

As Jeanne misrepresents herself to Sylvan through lies and distortions, the camera similarly represses sexuality through its selection of the moments of time it chooses to show or to omit. Although Akerman shoots much of the film in real time, the sex between Jeanne and her first two clients is not shown at all. Possibly, Akerman is seeking to avoid any audience voyeurism. Because sex is in itself often interesting, omitting it altogether from the film is one way to make it seem unimportant, to prevent any sexual titillation from creeping into the film. ... But by her failure to show Jeanne's physical prostitution, Akerman calls attention to it. She makes us not voyeurs but busybodies — we wonder what went on in the bedroom. By withholding knowledge of sex, she makes us preoccupied with it and forces us to identify not with Jeanne but with Sylvan, from whom knowledge is similarly withheld.

If we are to make real changes in our lives and in our cinema, we must offer not only new cinematic structures but serious solutions to the social problems that persist. If none are forthcoming, I feel it is better to be descriptive than prescriptive. Films which illustrate the extent of female oppression and the tenacity of patriarchy seem to me more feminist than those which offer cheap answers to complex social, historical and political problems - answers that fall within the range of acceptable responses as defined by male-dominated bourgeois culture. The sections of JEANNE DIELMAN which examine in minute detail the function and practice of housework and the role of the traditional mother within the repressive structure of the nuclear family are among the finest examples of feminist cinema yet produced, pioneering and carefully wrought in both form and content. I only wish Akerman had been content with this magnificent and unique achievement rather than succumbing to the demands of the traditional narrative film form that requires a bang-up ending and the culture that requires a neatly packaged and thoroughly acceptable message. In this case: Killing is good for you.

출처: https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC16folder/JeanneDielman.html

"Jeanne Dielman" by Jayne Loader

Jeanne Dielman Death in installments by Jayne Loader from Jump Cut, no. 16, 1977, pp. 10-12 copyright Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 1977, 2005 Chantal Akerman's JEANNE DIELMAN, 23 QUAI DU COMMERCE, 1080 BRUXELLES, recently subtitled in preparat

www.ejumpcut.org

In Jeanne Dielman, the camera is fixed and low (matching the filmmaker’s short height), and the frame composition is frontal and symmetrical. Akerman does not use close-ups, reverse angles, or point-of-view shots. She avoids cutting “this woman in pieces” and is “never voyeuristic,” she has explained, addressing the more feminist aspects of her project; one “always knows where I am.” Mangolte’s precise re-creation of light traversing an apartment through the day, and Seyrig’s contained portrayal, complement the director’s formal clarity.

A Matter of Time: Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce,1080 Bruxelles

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is Chantal Akerman’s masterpiece, a mesmerizing study of stasis and containment, time and domestic anxiety. Stretching its title character’s daily household routine in long, stark takes, Akerman’s

www.criterion.com

번역: https://siwff.tistory.com/667